‘Odyssey’ translator Emily Wilson called her a ‘passionate model of female power,’ but not every powerful woman deserves praise

https://electricliterature.com/is-homer ... -a-rapist/

Στο σποιλερ όλο το αρθρο

Women in this epic are undeniably powerful — without the aid of Athena, Nausicaa, Arete, or Ino, Odysseus would never have made it back to the shores of Ithaca. But women are dangerous as well, threatening the hero’s journey home. Odysseus must face and overcome Sirens, Scylla, Charybdis, Circe, and others.

Women in this epic are undeniably powerful — without the aid of Athena, Nausicaa, Arete, or Ino, Odysseus would never have made it back to the shores of Ithaca.

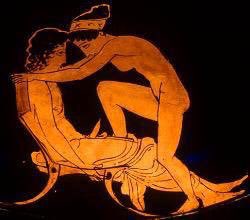

To me the most fascinating of Homer’s characters has always been Calypso, the goddess who saves Odysseus’s life and then imprisons him on her island for years. Calypso is terrifyingly dangerous — not unlike the other monstrous and elemental female opponents male heroes of Greek myth must meet and defeat in order to acquire their masculine bona fides, such as the Amazons, Harpies, Furies, and Medusa.

Feminists have rightly begun to see these vanquished women as figures ripe to be reclaimed. Electric Literature’s editor-in-chief Jess Zimmerman has penned a series of powerful essays for Catapult recovering myth’s marginalized female monsters. The figure of Medusa and her complex legacy in western thought loom large in Mary Beard’s newly published Women and Power, a history traced also by Elizabeth Johnston for The Atlantic. The mythical Amazons, defeated and “tamed” by heroes such as Hercules and Theseus, form the background myth for Wonder Woman, whose long-awaited film arrival this past summer was hailed by some (though by no means all) as a feminist victory. Emily Wilson herself has commented on the feminist potential of the Odyssey’s monsters to Bustle, “They’re presented in ways that are powerful…and very attractive and seductive.”

The human women of the Odyssey have likewise received feminist press recently. I myself have suggested that Penelope’s trick of weaving and unweaving a shroud to keep her suitors at bay foreshadows current feminist modes of resistance via craft — by this trick she is able to transform tools of oppression into tools of empowerment. But Penelope remains a woman in need of a patriarch, never allowed to attain to masculine power in her own right. And she in turn oppresses those women below her, the female slaves who, as we shall see, suffer violence with her sanction — a facet of Penelope that Wilson has rightly and repeatedly emphasized.

Penelope’s trick of weaving and unweaving a shroud to keep her suitors at bay foreshadows current feminist modes of resistance via craft — by this trick she is able to transform tools of oppression into tools of empowerment.

Wilson suggests, moreover, that if we are to see glimpses of real female power in the poem, we will find them not in its human but in its divine women:

There is a vision of empowered femininity in the Odyssey, but it is conveyed not in the mortal world but in that of the gods….The divine Calypso, Aphrodite, and Circe provide passionate models of female power — idealized fantasies of how much agency mortal women might have, if only social circumstances were completely different.

Such recognition of female power in the poem prompts one to ask whether Calypso is ready for a feminist recovery. My first inclination is to shout “yes!” to the skies — but to do so overlooks too much of what Homer tells us about her and the way she treats Odysseus.

Those artists and writers who do find in Calypso a sympathetic figure see her as a female lover abandoned and left alone, a frequent mythological predicament familiar to, say, Dido or Ariadne. In Ignorance, published in 2000, Milan Kundera writes:

Calypso, ah, Calypso! I often think about her. She loved Odysseus. They lived together for seven years. We do not know how long Odysseus shared Penelope’s bed, but certainly not so long as that. And yet we extol Penelope’s pain and sneer at Calypso’s tears.

A similar sentiment is found in Suzanne Vega’s 1987 song “Calypso,” narrated from the goddess’s point of view on the eve of Odysseus’s departure. She sings:

A long time ago

I watched him struggle with the sea

I knew that he was drowning

And I brought him in to me.

Now today

Come morning light

He sails away.

After one last night, I let him go…

I will stand upon the shore

With a clean heart…

It’s a lonely time ahead.

I do not ask him to return.

I let him go.

The elisions in these retellings, however, cannot be ignored. The Calypso episode is not a positive portrait of female power. Instead it shows us that asymmetrical and hierarchical power, no matter the biological sex of its wielder, masculinizes its possessor while subjugating and feminizing its victims. Calypso, like Penelope, exhibits oppressive behavior that severely compromises her feminist potential.

The matriarchal and patriarchal modes of power that are in competition with each other in the Calypso episode at first glance look quite different from one another. Hermes marvels as he arrives on Calypso’s island to deliver Zeus’s command that she let Odysseus go (a command omitted from the Kundera and Vega retellings). The lush landscape is a feast for the senses:

The scent of citrus and of brittle pine

suffused the island. Inside, she was singing

and weaving with a shuttle made of gold.

Her voice was beautiful. Around the cave

a luscious forest flourished: alder, poplar,

and scented cypress….

A ripe and luscious vine, hung thick with grapes,

was stretched to coil around her cave. Four springs

spurted with sparkling water as they laced

with crisscross currents intertwined together.

The meadow softly bloomed with celery

and violets. He gazed around in wonder

and joy, at sights to please even a god. (Wilson)

Greek thought constantly linked women to nature and men to cities and civilization. The fecundity of nature around Calypso’s cave signifies her unchecked feminine power. In an epic in which women’s voices emit dangerous siren songs, Calypso’s beautiful singing suggests everything here is under her sway. Her weaving is the activity par excellence of women in ancient myth, indicative of a fearsome feminine craftiness. The island is woman’s domain, Calypso’s natural cave utterly at odds with the kingly Olympian palace Hermes has just left, where the voice of authority belongs to Zeus. At first glance this island paradise is intensely seductive, the most tempting vision of feminist power the poem has to offer.

And yet, everyone Calypso keeps in her company is a slave — including Odysseus. It is clear that Calypso has imprisoned him: “Calypso, a great goddess, / had trapped him in her cave; she wanted him / to be her husband.” To be here means to be at the mercy of Calypso’s power.

What Calypso wants is not something new or different from masculine authority but her own feminine one to match it.

What Calypso wants is not something new or different from masculine authority but her own feminine one to match it. Chafing against Zeus’s command, she complains that goddesses are prohibited from enjoying the same dalliances with mortals that the male gods do: “You cruel, jealous gods! You bear a grudge / whenever any goddess takes a man / to sleep with as a lover in her bed….So now, you male gods are upset with me / for living with a man. A man I saved!” It is tempting to root for Calypso’s protest at this double standard. To quote Wilson in Bustle, “I love that the poem is able to at least have that moment where a female character is totally powerful and totally able to say, ‘There’s a problem with how we’re doing this.’” Or, similarly, John Peradotto, who states that Circe’s speech here “can be seen as representing revolt against a system whose order is made to depend on the suppression of female sexual desire in a way that is not expected of males.”

But of course the affairs male gods have with mortal women are often best described as rape, a term that likewise fits Calypso’s sexual domination of Odysseus as she replicates the very system with which she finds fault. Every day Odysseus weeps on the shore, powerless to leave:

His eyes were always

tearful; he wept sweet life away, in longing

to go back home, since she no longer pleased him.

He had no choice. He spent his nights with her

inside her hollow cave, not wanting her

though she still wanted him.

Some have sensed a poignant sorrow in these lines. Gregory Hays, in his New York Times review of Wilson’s translation, says that “we feel sadness on both sides” here. But I have difficulty mustering the same sympathy for Calypso as for Odysseus, who must sleep with the goddess without desire and without choice. My students, ready to condemn Odysseus for his faithless philandering, are always caught off guard by this passage. Put simply, Odysseus — like all victims of rape — does not have the power to say no. His daily weeping recalls that of his wife Penelope, who spends tearful days within the women’s quarters of her palace. If gender is defined not as biologically determined but as a culturally constructed phenomenon informed by power, then it is not Calypso but Odysseus who plays the woman’s part in this episode.

Put simply, Odysseus — like all victims of rape — does not have the power to say no.

As Mary Beard has ably demonstrated, “We have no template for what a powerful woman looks like, except that she looks rather like a man.” This is exceedingly true of Calypso in the Odyssey, who uses her divine authority in ways that replicate the nastiest aspects of patriarchal power, such as sexual domination and enslavement. As long as Calypso’s island mirrors Zeus’s own hierarchical structure, as long as she occupies the masculinized position of power, there are no feminist lessons to be learned here, only new iterations of the same ancient forms of male domination.

What of Odysseus, who learns how it feels to be a feminized victim of masculine power, who pines daily for his home and endures nightly sexual trauma? Does he learn to see things differently, to become a more just man upon his return? What does he want?

Calypso famously gives him a choice: leave and suffer new waves of human suffering or stay amid the luxuriant comforts of her island as a god — return to Penelope or stay Calypso’s forever. His choice is quick and clear: “I want to go back home, / and every day I hope that day will come.” Wilson in her introduction is highly attuned to the desire for power that informs this choice:

If Odysseus had stayed with Calypso, he would have been alive forever, and never grow old; but he would have been forever subservient to a being more powerful than himself. He would have lost forever the possibility of being king of Ithaca, owner of the richest and most dominant household on his island.

In other words, Odysseus’s choice is fueled not by a conviction that such unbalanced power is fundamentally wrong. He just wants it tipped in his favor. His experiences as a feminized slave have kindled his masculine desire to dominate.

Odysseus’s choice is fueled not by a conviction that such unbalanced power is fundamentally wrong. He just wants it tipped in his favor.

At first it seems as if the text offers a more hopeful possibility. After he leaves Calypso’s island, Odysseus encounters a terrible storm, washing up at last on the island of Phaeacia, where he encounters the teenage princess Nausicaa, who is ripe for marriage. He offers her a vision of marital concord at odds with the asymmetrical arrangement he’s just experienced with Calypso, one that bodes well for his reunion and future days with Penelope:

So may the gods grant all your heart’s desires,

a home and husband, somebody like-minded.

For nothing could be better than when two

live in one house, their minds in harmony,

husband and wife.

Perhaps Odysseus’ subjugation has taught him the severe shortcomings of unchecked authority, have rendered him able to imagine a way in which man and woman can live on egalitarian terms. Or perhaps, to quote Wilson again, he simply “has a strong ulterior motive for buttering [Nausicaa] up, since his life depends on her help.”

The text does not give us a clear answer, yet it continues to tempt us with the possibility that Odysseus has become sympathetic to the perspective of the subdued female. In one of the most famous similes of the epic, Odysseus, moved by the song of the Phaeacian bard Demodocus, cries like a woman whose husband has been killed in battle:

Odysseus was melting into tears;

his cheeks were wet with weeping, as a woman

weeps, as she falls to wrap her arms around

her husband, fallen fighting for his home

and children. She is watching as he gasps

and dies. She shrieks, a clear high wail, collapsing

upon his corpse. The men are right behind.

They hit her shoulders with their spears and lead her

to slavery, hard labor, and a life

of pain.

We might hope that Odysseus’s harrowing experience with Calypso has taught him something about what it means to be without agency. But of course it does not. In a scene that both Wilson and others have written about in the wake of the new translation, Odysseus brutally punishes the slave girls (not “maids” or “servants” or “sluts,” as the Greek is often rendered) who slept with the suitors overrunning his house in Ithaca. As classicist Yung In Chae observes, Wilson’s translation brings out (unlike many by men before her) the slave girls’ lack of agency: “The slightest alterations in translation can turn a girl into maid with few choices, a slave with none at all, or a slut who only has herself to blame. And it took a woman to see, or perhaps just care about, those differences.” But whereas Wilson’s female eyes can see the difference, Odysseus’s eyes, though feminized by his own experiences, cannot. He strings the slave girls up and hangs them for their disobedience to his absolute patriarchal authority over his house.

The Odyssey is, of course, a wonder to read, its women and men fantastical instantiations of intensely human fears and desires. In the end, though, there are few models of power in the Odyssey that anyone, feminists included, should be keen to embrace for our world today. Perhaps Odysseus’s intelligence and craftiness, like those of his wife Penelope, offer strategies to survive the experience of disempowerment, but they contain no long-term solution to fundamentally unjust hierarchies.

In the end, there are few models of power in the Odyssey that anyone, feminists included, should be keen to embrace for our world today.

Like its hero, Homer’s epic cannot imagine its way into a new paradigm even as it recognizes the precarious positions that women and the oppressed too often find themselves in. Though it fails to offer better solutions, it does have lessons to teach about the damaging ways authority gets wielded and about those who unjustly get to wield it — and perhaps that is why we should all read it, for its negative rather than positive representations of power so that we can be on guard against them.

I do not want a feminist hero who merely refashions masculine tools of oppression as her own. To quote Audre Lorde’s landmark feminist essay:

For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.

Or, to quote Mary Beard, “You cannot easily fit women into a structure that is already coded as male; you have to change the structure. That means thinking about power differently.” Calypso offers not a hopeful possibility for women but a warning to any woman who climbs the tiers of power without questioning or transforming the asymmetrical system that keeps women as a whole in check. If the structure is not changed, in can waltz Hermes, armed with Zeus’s authoritative command, to overpower you in turn. As long as it is built upon the oppression of others, the same hierarchy that at one moment works for you can now work against you. Unlike Odysseus, we can choose to really see ourselves in the disempowered and by doing so change who we are for the better. That is the challenge for anyone reading the Odyssey today.

While I wholeheartedly embrace the refashioning of myth’s female monsters as our own, I do not want to find feminist empowerment where it should not be, a new female face superimposed upon the same old tale. As much as I love these old Greek stories and always will, we all desperately deserve a new one.