Μα πως είναι δυνατόν να συμβάλουν οι κλανιές των αγελάδων στην κλιματική αλλαγή;Part of the issue The 100-year-old-mistake that’s reshaping the American West from The Highlight, Vox’s home for ambitious stories that explain our world.

Last May, 30 miles east of the Las Vegas Strip, a barrel containing a dead body washed up on the shores of Lake Mead, the country’s largest water reservoir. In the following months, more human remains surfaced, along with a World War II-era boat and dozens of other vessels.

While these discoveries might sound like the opening to a crime thriller, they’re more than just morbid curiosities — they’re flashing warning signs that the Colorado River, which supplies water and hydropower to 40 million Americans, is in crisis.

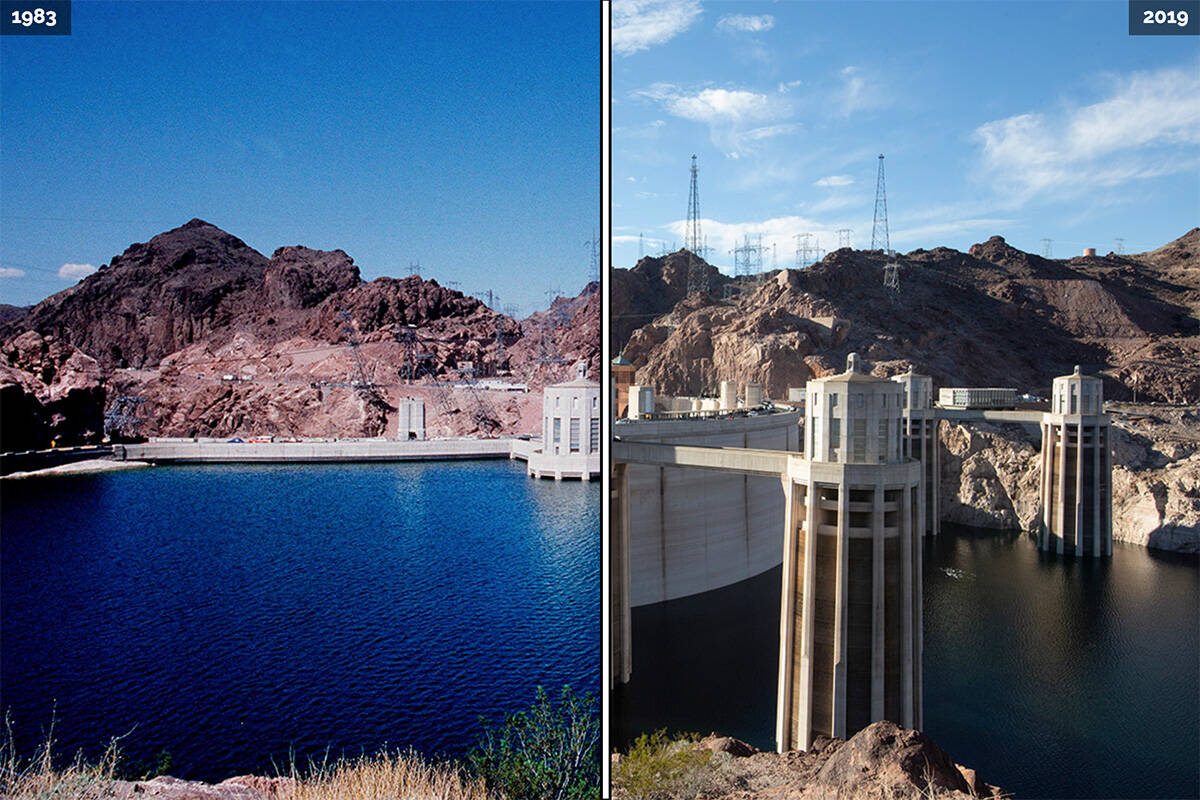

Along with Lake Powell 300 miles away, Lake Mead stores water for the lower states along the Colorado River: California, Arizona, and Nevada as well as Mexico and around 20 Indigenous reservations. But a climate change-induced “megadrought” has led to higher rates of water evaporation in recent decades and a drastic reduction in water supply, with Lake Mead currently at just 29 percent capacity. The streamflow on the northern part of the river, which supplies Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, and five Indigenous reservations, has fallen 20 percent over the last century.

Heavy snowfall in the Rocky Mountains this winter should give Lake Powell a modest boost as it melts, but not enough to assuage fears over the lakes reaching what’s termed “dead pool” status, when water levels drop too low to flow through the dams. To avoid that fate, the federal government has urged states to cut their water use.

But despite news stories about drought-stricken Americans in the West taking shorter showers and ditching lawns to conserve their water supply, those efforts are unlikely to amount to much — residential water use accounts for just 13 percent of water drawn from the Colorado River. According to research published in Nature Sustainability, the vast majority of water is used by farmers to irrigate crops.

And when you zoom in to look at exactly which crops receive the bulk of the Colorado River’s water, 70 percent goes to alfalfa, hay, corn silage, and other grasses that are used to fatten up cattle for beef and cows for dairy. Some of the other crops, like soy, corn grain, wheat, barley, and even cotton, may also be used for animal feed.

“Meat production is the most environmentally stressful thing people do, and reducing it would make a huge impact on the planet,” said Ben Ruddell, a professor of informatics and computing at Northern Arizona University and co-author of the Nature Sustainability paper, over email to Vox. “We’ve known this for a long time.”

The stress on the West’s water supply due to alfalfa is especially acute in Utah: A staggering 68 percent of the state’s available water is used to grow alfalfa for livestock feed, even though it’s responsible for a tiny 0.2 percent of the state’s income. Last year, the editorial board of the state’s largest newspaper, the Salt Lake Tribune, declared that “it’s time for Utah to buy out alfalfa farmers and let the water flow.”

California takes more water from the Colorado River than any other state, and most of it goes to the Imperial Valley in the southern part of the state. It’s one of the most productive agricultural regions in the US, producing two-thirds of America’s vegetables during winter months. But the majority of the Imperial Valley’s farmland is dedicated to alfalfa and various grasses for livestock.

In Arizona, Phoenix’s backup water supply is being drained to grow alfalfa by Fondomonte, owned by Saudi Arabia’s largest dairy company, which it ships 8,000 miles back to the Middle East to feed its domestic herds. (Water-starved Saudi Arabia banned growing alfalfa and some other animal feed crops within its own borders in 2018.) Across the 17 Western states, at least 10 percent of alfalfa is shipped to Asia and the Middle East where meat and dairy consumption is low compared to the US but on the rise.

A drought is the product of two interlocking factors: supply and demand. We can point to climate change for the drought that’s drying up the water supply that is the Colorado River, but we have to reckon with the fact that the West’s already limited water is primarily used to grow a low-value crop, alfalfa, while cities are left to spend heavily on water-saving infrastructure to keep the H2O running and ensure reserves. And ironically, all that alfalfa is used to produce beef and dairy — two food groups that themselves contribute significantly to climate change. In other words, we’re using water supplies that have been shrunk in part by climate change to produce food that will in turn worsen climate change.

The West’s water squeeze can be explained by poor planning in its past, but it raises a difficult question for its future: As local and state governments are forced to adapt their water use to a changing climate, do we also need to start thinking about adapting our diets?

When I asked John Matthews, executive director of the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation, why there are so many water-intensive farming operations in the desert ecosystem of the Southwestern US, he had a simple answer: If we could start from scratch, we would not have designed the system we have today.

“I don’t think a farmer would design it this way,” he said.

The West’s water system has its roots in the 1862 federal Homestead Act, which gave Western settlers up to 160 acres of land for free if they agreed to improve it and stay on it for at least five years, and later offered even more land at a reduced price if they agreed to farm it. But because there was so little water and irrigation was shoddy, Congress passed the Reclamation Act in 1902 to “reclaim” arid land in the West for agriculture. The federal government sold tracts of land to fund massive irrigation damming projects to divert rivers and streams to farms. Armed with cheap land and water backed by federal price guarantees — and aided by a warm climate that permitted an expanded growing season — Western settlers began to farm cotton and alfalfa.

Choosing to put farms on arid land wasn’t the only short-sighted mistake the region made. In 1922, negotiators representing the seven states that share the river’s water grossly overestimated just how much water it could provide, which locked in over-apportionment and thus overuse.

Of course, government officials at the time also couldn’t foresee a historic, climate change-fueled drought, or the growth of sprawling metropolises like Phoenix and Las Vegas in the decades to come that would compete with agriculture for limited resources. (In 1920, Arizona’s total population was just 334,000 people — around 20 percent of Phoenix’s current population — while all of Nevada had only 77,000 people.)

And most importantly — and at the heart of the conflict today between California and its fellow Colorado River users — is how water rights were obtained.

In the Eastern US, water rights are determined using what’s called the riparian doctrine — everyone who lives near a body of water has an equal right to use it, and is entitled to a “reasonable use” of it. The Western US, as is the case in so many other areas, does things differently.

Water rights in the West were determined — under state laws — by what’s called the prior appropriation doctrine, which gives senior water rights to whoever first uses the water, a right they retain so long as they continue to use it. And those rights were mostly snatched up by miners during the Gold Rush era of the mid-1800s and farmers in the following decades who came to the West after the Homestead and Reclamation Acts (and some of that water and land was taken from Indigenous tribes). Even in times of shortage, senior water rights holders — many of them farmers — get priority over latecomers, like those millions of Western urbanites.

That created repeated conflict — as the old Western saying goes, “Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting.” Over 150 years after the Gold Rush, fights over the prior appropriation doctrine are as fierce as ever, playing out in communities and between states, like Cochise County, Arizona, residents battling a water-guzzling mega-dairy, or the six Colorado River states that have agreed to slash their use to make up for the shortfall while California refuses to commit to necessary reductions. It’s now the Golden State versus everyone else.

California public officials, like many California farmers, argue that they don’t need to cut their water use so drastically because they hold senior rights. That’s now up in the air. Earlier this month, the Department of the Interior published a draft analysis detailing three options it can take if states fail to reach an agreement: do nothing, make cuts based on existing water rights, or cut water allotments evenly among California, Arizona, and Nevada.

“This is what we have inherited: a very rigid and complex system,” said Nick Hagerty, an assistant professor of agricultural economics at Montana State University, back in February.

Matthews was blunter: “It is a stupid system, but the problem is that people are really heavily invested in that system.”

However, it’s hard to get those who’ve benefited from the system for so long to change. California’s Imperial Valley, home to many alfalfa farms, gets about as much water from the Colorado River as the entire state of Arizona — and farmers in the Valley pay just $20 per acre foot (326,000 gallons). Meanwhile, farmers and residents in nearby San Diego County pay around $1,000 or more per acre-foot.

Many Imperial Valley farmers are reluctant to reduce their use, citing their senior water rights. One farmer who chairs an agricultural water committee for the valley’s water district told Cal Matters that unless the federal government adequately compensates farmers, mandated cuts could be akin to property theft, and blamed water shortages on urban growth and excessive use from junior water rights holders.

The Imperial Irrigation District now conserves around 15 percent of its allocation, though much of that conservation is funded by San Diego County, which receives some water from the district.

Sudden changes to the water supply can hit farmers hard, and assistance has taken various forms in recent years — and experts like Matthews want to see them get the help they need to adapt to a different, drier economy. As the US Bureau of Reclamation has reduced the water supply for several states and Mexico, a patchwork of federal and state initiatives have moved forward to compensate farmers to reduce water use.

Late last year, the Biden administration announced it will use some of the $4 billion in drought mitigation from the Inflation Reduction Act to pay farmers — as well as cities and Indigenous tribes — to cut their water use. Utah lawmakers recently proposed spending $200 million on grants for farmers to invest in promising but costly water-saving technologies, while farmers in Southern California have been paid to skip planting some of their fields.

But Hagerty says a lot more could be done: “I think it’s incredibly important there be more flexibility in the system.” He wants to see farmers have more leeway to transfer, sell, or lease their water rights to cities. In California, farmers don’t directly hold their water rights and instead are members of irrigation districts that collectively hold those rights. But California law often impedes the districts from leasing water, leading some farmers to use water even if it may not be critical to their operations because if they don’t use it, they lose it.

One solution he’s proposed is a reverse auction, in which water users make bids to the federal government on how much money they’d accept to forgo a particular amount of water use. But he says any reform will inevitably be incremental because there are so many competing interests at play.

“Policymakers have been hesitant to make any real major changes, and I think that’s partly because this stuff is very politically fraught,” Hagerty said. “There’s a whole lot of different stakeholders to keep happy.”

Adapting to climate change includes changing what we eat

A number of short-term solutions should be enough to help Colorado River states get through the next few years, but in the long term, policymakers and food producers — and us — around the world will need to rethink how we farm and eat in a changing climate. It won’t be enough to simply change farming practices in the Western US, as Ruddell, a co-author of the Nature Sustainability paper, noted to me.

That means altering the demand side of the water supply-demand equation and shifting diets globally to foods that use less H2O, which ultimately means less meat and dairy, as well as fewer water-intensive tree nuts like almonds, pistachios, and cashews (nut milks, however, require much less water to produce than cow’s milk).

Agriculture isn’t just the largest user of water in the Southwestern US, it’s the largest globally, consuming 70 percent of freshwater withdrawals. And what we need in the Southwest and beyond isn’t just climate adaptation, but dietary adaptation.

Just as policymakers made the Western US into the agricultural powerhouse it is today, despite its lack of something that is generally considered key to farming — water — they can also shape water policy and broader agricultural policy to ensure water security for the tens of millions of Americans west of the Mississippi River. But that will require policy changes that go beyond the dinner table.

The federal government, through deregulation, R&D investments, subsidies, and food purchasing (like for public schools and federal cafeterias), heavily favors animal agriculture. Given the meat and dairy lobby’s political influence and farm states’ overrepresentation in the Senate, drastic changes to our food supply in the near term, ones that would favor plant-based agriculture, are out of the realm of political possibility. But change is afoot: In March, the Biden administration announced goals to bolster R&D for plant-based meat and dairy and other animal-free food technologies. Down the road, climate change may force some state and federal government’s hands to turn those goals into comprehensive agriculture policy. Already, American policymakers are mulling and making hard choices about water use, pitting crops for cows against water for people.

There’s no disagreement that if the Colorado River can continue to supply Americans with running water, there will need to be cuts to agricultural use. We can learn from the mistakes made by Western planners in 1922 who overestimated how much water would flow from the Colorado River, and act now to shape food policy to adapt to a warming, drier climate.

Special thanks to Laura Bult and Joss Fong on the Vox video team, whose extensive research for a November 2022 video on this subject contributed to this story.

https://www.vox.com/platform/amp/the-hi ... -beef-meat

Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

ΣΑΤΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΕΓΚΕΦΑΛΟΣ έγραψε: ↑05 Ιούλ 2020, 12:19Η διάρροια του μπακογιάννη μετά από οξεία τροφική δηλητηρίαση είναι νέκταρ και αμβροσία

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

δεν είναι λέει βιώσιμη η εκτροφή γιγαντιαίων μονάδων εκτροφής βοοειδών στην έρημο. Είναι δυνατόν;

ΣΑΤΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΕΓΚΕΦΑΛΟΣ έγραψε: ↑05 Ιούλ 2020, 12:19Η διάρροια του μπακογιάννη μετά από οξεία τροφική δηλητηρίαση είναι νέκταρ και αμβροσία

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

ΣΑΤΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΕΓΚΕΦΑΛΟΣ έγραψε: ↑05 Ιούλ 2020, 12:19Η διάρροια του μπακογιάννη μετά από οξεία τροφική δηλητηρίαση είναι νέκταρ και αμβροσία

- Lt Aldo Raine

- Δημοσιεύσεις: 262

- Εγγραφή: 08 Ιουν 2023, 10:04

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

“Meat production is the most environmentally stressful thing people do, and reducing it would make a huge impact on the planet,” said Ben Ruddell, a professor of informatics and computing at Northern Arizona University and co-author of the Nature Sustainability paper, over email to Vox. “We’ve known this for a long time.”

Ένας,δύο,πολλοί Φέργκουσον.

Ένας,δύο,πολλοί Φέργκουσον.

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

Οι πίτες δε λενε ψέματα κύριε ΓκορλόμιLt Aldo Raine έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 12:12“Meat production is the most environmentally stressful thing people do, and reducing it would make a huge impact on the planet,” said Ben Ruddell, a professor of informatics and computing at Northern Arizona University and co-author of the Nature Sustainability paper, over email to Vox. “We’ve known this for a long time.”

Ένας,δύο,πολλοί Φέργκουσον.

ΣΑΤΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΕΓΚΕΦΑΛΟΣ έγραψε: ↑05 Ιούλ 2020, 12:19Η διάρροια του μπακογιάννη μετά από οξεία τροφική δηλητηρίαση είναι νέκταρ και αμβροσία

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

ΣΑΤΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΕΓΚΕΦΑΛΟΣ έγραψε: ↑05 Ιούλ 2020, 12:19Η διάρροια του μπακογιάννη μετά από οξεία τροφική δηλητηρίαση είναι νέκταρ και αμβροσία

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

Στηριζουμε το κλεισιμο τον μοναδων εκτροφης και την αποβιομηχανοποιηση. Τα ζωντανα απο τον λαο, για τον λαο.

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

φταιει το συστημα των εξαγωγων ας μην εξαγει σε ολο τον κοσμο δημητριακα και κρεας

υσ...το να σταματησουν τις κλανιες δεν θα κερδισουν τιποτα μακροπροσθεσμα

ισα ισα που θα μεγεθυνουν το προβλημα

υσ...το να σταματησουν τις κλανιες δεν θα κερδισουν τιποτα μακροπροσθεσμα

ισα ισα που θα μεγεθυνουν το προβλημα

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

ΣΑΤΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΕΓΚΕΦΑΛΟΣ έγραψε: ↑05 Ιούλ 2020, 12:19Η διάρροια του μπακογιάννη μετά από οξεία τροφική δηλητηρίαση είναι νέκταρ και αμβροσία

-

Δημοκράτης

- Δημοσιεύσεις: 24831

- Εγγραφή: 25 Ιαν 2019, 00:26

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

Ε οκ μπορούμε να πεθάνουμε της πείναςΣενέκας έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 12:18Οι πίτες δε λενε ψέματα κύριε ΓκορλόμιLt Aldo Raine έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 12:12“Meat production is the most environmentally stressful thing people do, and reducing it would make a huge impact on the planet,” said Ben Ruddell, a professor of informatics and computing at Northern Arizona University and co-author of the Nature Sustainability paper, over email to Vox. “We’ve known this for a long time.”

Ένας,δύο,πολλοί Φέργκουσον.

Λογικά πραγματα

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

αν διάβαζες το άρθρο θα έβλεπες ότι αυτό που λογίζεται ως αγροτική παραγωγή στην περιοχή, δεν είναι τρόφιμα για ανθρώπους, είναι χαμηλής απόδοσης καρποί, ψυχανθές και αλφάλφα που χρησιμοποιούνται ως τροφή για τις φάρμες βοοειδών. Μια πηγή καθαρού νερού που εξυπηρετεί 40 μύρια πληθυσμό και 6 πολιτείες στερεύει γιατί έχει χτιστεί όλο το σύστημα με στόχο να εξυπηρετεί την αγροτική παραγωγή στην έρημο, που συντηρεί τις φάρμες βοοειδώνΔημοκράτης έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 14:56Ε οκ μπορούμε να πεθάνουμε της πείναςΣενέκας έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 12:18Οι πίτες δε λενε ψέματα κύριε ΓκορλόμιLt Aldo Raine έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 12:12“Meat production is the most environmentally stressful thing people do, and reducing it would make a huge impact on the planet,” said Ben Ruddell, a professor of informatics and computing at Northern Arizona University and co-author of the Nature Sustainability paper, over email to Vox. “We’ve known this for a long time.”

Ένας,δύο,πολλοί Φέργκουσον.

Λογικά πραγματα

ΣΑΤΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΕΓΚΕΦΑΛΟΣ έγραψε: ↑05 Ιούλ 2020, 12:19Η διάρροια του μπακογιάννη μετά από οξεία τροφική δηλητηρίαση είναι νέκταρ και αμβροσία

-

Δημοκράτης

- Δημοσιεύσεις: 24831

- Εγγραφή: 25 Ιαν 2019, 00:26

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

Που ως γνωστόν μετά οι αγελάδες δεν παράγουν τροφή για τον άνθρωποΣενέκας έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 15:04αν διάβαζες το άρθρο θα έβλεπες ότι αυτό που λογίζεται ως αγροτική παραγωγή στην περιοχή, δεν είναι τρόφιμα για ανθρώπους, είναι χαμηλής απόδοσης καρποί, ψυχανθές και αλφάλφα που χρησιμοποιούνται ως τροφή για τις φάρμες βοοειδών. Μια πηγή καθαρού νερού που εξυπηρετεί 40 μύρια πληθυσμό και 6 πολιτείες στερεύει γιατί έχει χτιστεί όλο το σύστημα με στόχο να εξυπηρετεί την αγροτική παραγωγή στην έρημο, που συντηρεί τις φάρμες βοοειδών

- Dwarven Blacksmith

- Δημοσιεύσεις: 43159

- Εγγραφή: 31 Μαρ 2018, 18:08

- Τοποθεσία: Maiore Patria

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

Όλοι ξέρουν ότι αν πέσει αρκετά, θα κάνει instant respawn ο υδροφόρος ορίζοντας. Δεν χρειάζεται δεκαετίες or anything. Απλά μας τρομάζουν για να μας πάρουν τα λεφτουδακια μας. Μια φορά δεν έχουν έρθει να πούνε "βρήκα αυτό το πρόβλημα, αλλά μην ανησυχείτε, μέχρι αύριο θα έχω φτιάξει τζάμπα".

I would have lived in peace. But my enemies brought me war.

I would have lived in peace. But my enemies brought me war.

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

αυτό λέμε....Δημοκράτης έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 15:06Που ως γνωστόν μετά οι αγελάδες δεν παράγουν τροφή για τον άνθρωποΣενέκας έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 15:04αν διάβαζες το άρθρο θα έβλεπες ότι αυτό που λογίζεται ως αγροτική παραγωγή στην περιοχή, δεν είναι τρόφιμα για ανθρώπους, είναι χαμηλής απόδοσης καρποί, ψυχανθές και αλφάλφα που χρησιμοποιούνται ως τροφή για τις φάρμες βοοειδών. Μια πηγή καθαρού νερού που εξυπηρετεί 40 μύρια πληθυσμό και 6 πολιτείες στερεύει γιατί έχει χτιστεί όλο το σύστημα με στόχο να εξυπηρετεί την αγροτική παραγωγή στην έρημο, που συντηρεί τις φάρμες βοοειδών

ΣΑΤΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΕΓΚΕΦΑΛΟΣ έγραψε: ↑05 Ιούλ 2020, 12:19Η διάρροια του μπακογιάννη μετά από οξεία τροφική δηλητηρίαση είναι νέκταρ και αμβροσία

Re: Οι κλανιές των αγελάδων και ο Ποταμός Κολοράντο

μέσα έπεσεςDwarven Blacksmith έγραψε: ↑23 Ιούλ 2023, 15:07Όλοι ξέρουν ότι αν πέσει αρκετά, θα κάνει instant respawn ο υδροφόρος ορίζοντας. Δεν χρειάζεται δεκαετίες or anything. Απλά μας τρομάζουν για να μας πάρουν τα λεφτουδακια μας. Μια φορά δεν έχουν έρθει να πούνε "βρήκα αυτό το πρόβλημα, αλλά μην ανησυχείτε, μέχρι αύριο θα έχω φτιάξει τζάμπα".

Concerns over the Colorado River have led the everyday Arizonan to think about water in ways they haven’t before. As a result, much has been made as of late about growing “thirsty crops” in Arizona’s desert climate. It doesn’t take long to find an opinion or editorial about how farming alfalfa is the embodiment of everything that is wrong with the water system in Arizona.

This rhetoric needs to stop. Here’s why.

When you hear that agriculture uses nearly three-fourths of Arizona’s water, it is easy to draw the conclusion that the best way to save water for growing urban populations is to take it from the largest user. In reality, though, that water is already being consumed by that urban population each and every time they sit down for a meal.

While you and I don’t regularly enjoy a flake of alfalfa for breakfast, alfalfa is a major contributor to something we do rely on as a nutritional staple: milk. According to United Dairymen of Arizona, 70% of all the milk produced in Arizona is consumed directly by Arizona customers, including Kroger, Albertsons, Daisy Sour Cream, and Fairlife. In fact, 97% of the milk sold in Arizona grocery stores comes from an Arizona family dairy, regardless of the brand under which it’s sold. Our Arizona dairymen are some of the most efficient milk producers in the world. These efficiencies are made possible by harnessing the benefits of a desert climate, improved genetics in dairy cattle and, importantly, high-quality feed.

Not all alfalfa is created, well-produced, equally

That may beg the question: why not import that feed from somewhere else? But that question assumes all alfalfa is produced equally. Nothing is further from the truth. Arizona’s alfalfa yields are among the highest in the world. Our farmers produce an average of 8.3 tons of alfalfa per acre, compared to the nationwide average of 3.2 tons. That’s largely because our climate gives us a competitive advantage in growing these crops. To grow them anywhere else would require more land, more fossil fuel resources, and, yes, more water.

Our dairy industry didn’t locate here by happenstance. It came here because our climate facilitates efficiencies that create a strategic advantage for the effectiveness of the industry. Our dairies must be located close to markets in Phoenix to provide the liquid milk, yogurt, cheese and other dairy products consumed by a growing population at a cost that population can afford, and it has developed a local supply of critical inputs in order to maximize efficiency.

In any other commercial venture, that strategic advantage would be celebrated with ribbon cuttings and presidential site visits. Why do we villainize it when it relates to food production?

Rather than asking whether we should be growing “thirsty crops,” perhaps we should be asking how we are going to feed and clothe our hungry cities. Better yet, we should be asking how we find a sustainable balance for everyone. A water crisis solution that leads to a food supply crisis is no solution at all.

About Arizona Farm Bureau

The Arizona Farm Bureau is a grassroots organization dedicated to preserving and improving the agriculture industry through member involvement in advocacy, communication and education that include programs and services to support our Arizona farmers and ranchers and our 25,000 members. For information on member benefits call 480.635.3609. For recipes, farmers markets, farm products and farms to visit, go to Arizona Farm Bureau’s www.fillyourplate.org. Also, visit www.azfb.org/water.

Chelsea McGuire is the Arizona Farm Bureau Government Relations Director.

https://azcapitoltimes.com/news/2023/01 ... is-no-fix/

ΣΑΤΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΕΓΚΕΦΑΛΟΣ έγραψε: ↑05 Ιούλ 2020, 12:19Η διάρροια του μπακογιάννη μετά από οξεία τροφική δηλητηρίαση είναι νέκταρ και αμβροσία

-

- Παραπλήσια Θέματα

- Απαντήσεις

- Προβολές

- Τελευταία δημοσίευση

-

-

Νέα δημοσίευση Νέα Ζηλανδία: Φόρος σε κλανιές και ρεψίματα (αγελάδων)

από Orion22 » 13 Οκτ 2022, 19:20 » σε Διεθνής πολιτική - 0 Απαντήσεις

- 219 Προβολές

-

Τελευταία δημοσίευση από Orion22

13 Οκτ 2022, 19:20

-

-

-

Νέα δημοσίευση Στύγα: Η Γυναίκα- Ποταμός που ΕΞΟΝΤΩΝΕ τους Θεούς! | The Mythologist

από tanipteros » 18 Ιουν 2022, 13:25 » σε Θρησκειολογία - 7 Απαντήσεις

- 466 Προβολές

-

Τελευταία δημοσίευση από Juno

18 Ιουν 2022, 20:36

-

-

-

Νέα δημοσίευση Γουστάρετε να μυρίζετε τις κλανιές σας;

από Μαδουραίος » 22 Ιούλ 2023, 16:37 » σε Περί ανέμων και υδάτων - 2 Απαντήσεις

- 231 Προβολές

-

Τελευταία δημοσίευση από George_V

22 Ιούλ 2023, 16:52

-

-

-

Νέα δημοσίευση Γιατί ο Λαζόπουλος είχε τέτοια εμμονή με τις κλανιές;

από Εκτωρ » 11 Ιουν 2022, 23:39 » σε 7η τέχνη και Ηλ. ΜΜΕ - 7 Απαντήσεις

- 530 Προβολές

-

Τελευταία δημοσίευση από taliban

12 Ιουν 2022, 00:24

-