αυτιστικότητα....Αρίστος έγραψε: ↑13 Ιουν 2024, 10:06Μαθαινε τρομπα.Αρίστος έγραψε: ↑13 Ιουν 2024, 09:57

Η ζωφόρος έφτασε στο μορφολογικό της απόγειο στη μοναδική περίπτωση του τέταρτου Παρθενώνα (της κλασικής περιόδου του πέμπτου π.Χ.αιώνα), ο οποίος όμως πρόκειται για τη συνύπαρξη των δύο αρχιτεκτονικών ρυθμών, στην πόλη των Αθηνών, η οποία πρόκειται για ιωνική πόλη καθώς οι Αθηναίοι αυτοπροσδιορίζονταν ως Ίωνες.

https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/%CE%96%CF ... E%BF%CF%82

.

Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

- taxalata xalasa

- Δημοσιεύσεις: 20703

- Εγγραφή: 27 Αύγ 2021, 20:52

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Πολλών δ’ ανθρώπων ίδεν άστεα και νόον έγνων.

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Είμαι στην δεύτερη σελίδα. Την εκδοχή της αλληγορίας την έχουμε απορρίψει τελείως και καταλήγουμε πως οι Άτλαντες ήταν γίγαντες γιάνκιδες. Λογικά κάπου στην 10η σελίδα θα έρθουν και οι αποδείξεις πως οι Άτλαντες ήταν οι πρώτοι μπασκετμπολίστες του NBA.

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Αντε να βαλουμε και το λουκουμο στο νημα.

Ενα σκασμο αρχαιους Ελληνες και Ρωμαιους λογιους που οχι μονο θεωρουσαν σαν αληθινη την ιστορια του Πλατωνα για την Ατλαντιδα αλλα καποιοι συμπληρωσαν και επιπλεον στοιχεια.

Κανονιστε γιδια να τους βγαλετε ψεκες, θεοσοφιστες η ναζι.

Syrianus (died c.437 BC) the neoplatonist and one-time head of Plato’s Academy in Athens, considered Atlantis to be an historical fact. He wrote a commentary on Timaeus, now lost, but his views are recorded by Proclus.

Eumelos of Cyrene (c.400 BC) was a historian and contemporary of Plato’s who placed Atlantis in the central Mediterranean between Libya and Sicily.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Plato’s pupil is constantly quoted in connection with his alleged criticism of Plato’s story. This claim was not made until 1819, when Delambre misinterpreted a commentary on Strabo by Isaac Casaubon. This error has been totally refuted by Thorwald C. Franke[880]. Furthermore it was Aristotle who stated that the Phoenicians knew of a large island in the Atlantic known as ’Antilia’.

Crantor (4th-3rdcent. BC) was Plato’s first editor who reported visiting Egypt where he claimed to have seen a marble column carved with hieroglyphics about Atlantis.

Theophrastus of Lesbos (370-287 BC) refers to colonies of Atlantis in the sea.

Theopompos of Chios (born c.380 BC), a Greek historian – wrote of the huge size of Atlantis and its cities of Machimum and Eusebius and a golden age free from disease and manual labour. Zhirov states [458.38/9] that Theopompos was considered a fabulist.

Apollodorus of Athens (fl. 140 BC) who was a pupil of Aristarchus of Samothrace (217-145 BC) wrote “Poseidon was very wrathful, and flooded the Thraisian plain, and submerged Attica under sea-water.” Bibliotheca, (III, 14, 1.)

Poseidonius (135-51 BC.) was Cicero’s teacher and wrote, “There were legends that beyond the Hercules Stones there was a huge area which was called “Poseidonis” or “Atlanta”

Diodorus Siculus (1stcent. BC), the Sicilian writer who has made a number of references to Atlantis.

Marcellus (c.100 BC) in his Ethiopic History quoted by Proclus [Zhirov p.40] refers to Atlantis consisting of seven large and three smaller islands.

Statius Sebosus (c. 50 BC), the Roman geographer, tells us that it was forty days’ sail from the Gorgades (the Cape Verdes) and the Hesperides (the Islands of the Ladies of the West, unquestionably the Caribbean).

Timagenus (c.55 BC), a Greek historian wrote of the war between Atlantis and Europe and noted that some of the ancient tribes in France claimed it as their original home. There is some dispute about the French druids’ claim.

Philo of Alexandria (b.15 BC) also known as Philo Judaeus also accepted the reality of Atlantis’ existence.

Strabo (67 BC-23 AD) in his Geographia stated that he fully agreed with Plato assertion that Atlantis was fact rather than fiction.

Plutarch (46-119 AD) wrote about the lost continent in his book Lives, he recorded that both the Phoenicians and the Greeks had visited this island which lay on the west end of the Atlantic.

Pliny the Younger (61-113 AD) is quoted by Frank Joseph as recording the existence of numerous sandbanks outside the Pillars of Hercules as late as 100 AD.

Pomponius Mela (c.100 AD), placed Atlantis in a southern temperate region.

Tertullian (160-220 AD) associated the inundation of Atlantis with Noah’s flood.

Claudius Aelian (170-235 AD) referred to Atlantis in his work The Nature of Animals.

Arnobius (4thcent. AD.), a Christian bishop, is frequently quoted as accepting the reality of Plato’s Atlantis.

Ammianus Marcellinus (330-395 AD), the Greek historian, who wrote about the destruction of Atlantis as an accepted fact by the intelligentsia of Alexandria.

Proclus Lycaeus (410-485 AD), a representative of the Neo-Platonic philosophy, recorded that there were several islands west of Europe. The inhabitants of these islands, he proceeds, remember a huge island that they all came from and which had been swallowed up by the sea. He also writes that the Greek philosopher Crantor saw the pillar with the hieroglyphic inscriptions, which told the story of Atlantis.

Cosmas Indicopleustes (6thcent. AD), a Byzantine geographer, in his Topographica Christiana (547 AD) quotes the Greek Historian, Timaeus (345-250 BC) who wrote of the ten kings of Chaldea [Zhirov p.40]. *[Marjorie Braymer[198.30] wrote that Cosmas was the first to use Plato’s Atlantis to support the veracity of the Bible.]*

.

Ενα σκασμο αρχαιους Ελληνες και Ρωμαιους λογιους που οχι μονο θεωρουσαν σαν αληθινη την ιστορια του Πλατωνα για την Ατλαντιδα αλλα καποιοι συμπληρωσαν και επιπλεον στοιχεια.

Κανονιστε γιδια να τους βγαλετε ψεκες, θεοσοφιστες η ναζι.

Syrianus (died c.437 BC) the neoplatonist and one-time head of Plato’s Academy in Athens, considered Atlantis to be an historical fact. He wrote a commentary on Timaeus, now lost, but his views are recorded by Proclus.

Eumelos of Cyrene (c.400 BC) was a historian and contemporary of Plato’s who placed Atlantis in the central Mediterranean between Libya and Sicily.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Plato’s pupil is constantly quoted in connection with his alleged criticism of Plato’s story. This claim was not made until 1819, when Delambre misinterpreted a commentary on Strabo by Isaac Casaubon. This error has been totally refuted by Thorwald C. Franke[880]. Furthermore it was Aristotle who stated that the Phoenicians knew of a large island in the Atlantic known as ’Antilia’.

Crantor (4th-3rdcent. BC) was Plato’s first editor who reported visiting Egypt where he claimed to have seen a marble column carved with hieroglyphics about Atlantis.

Theophrastus of Lesbos (370-287 BC) refers to colonies of Atlantis in the sea.

Theopompos of Chios (born c.380 BC), a Greek historian – wrote of the huge size of Atlantis and its cities of Machimum and Eusebius and a golden age free from disease and manual labour. Zhirov states [458.38/9] that Theopompos was considered a fabulist.

Apollodorus of Athens (fl. 140 BC) who was a pupil of Aristarchus of Samothrace (217-145 BC) wrote “Poseidon was very wrathful, and flooded the Thraisian plain, and submerged Attica under sea-water.” Bibliotheca, (III, 14, 1.)

Poseidonius (135-51 BC.) was Cicero’s teacher and wrote, “There were legends that beyond the Hercules Stones there was a huge area which was called “Poseidonis” or “Atlanta”

Diodorus Siculus (1stcent. BC), the Sicilian writer who has made a number of references to Atlantis.

Marcellus (c.100 BC) in his Ethiopic History quoted by Proclus [Zhirov p.40] refers to Atlantis consisting of seven large and three smaller islands.

Statius Sebosus (c. 50 BC), the Roman geographer, tells us that it was forty days’ sail from the Gorgades (the Cape Verdes) and the Hesperides (the Islands of the Ladies of the West, unquestionably the Caribbean).

Timagenus (c.55 BC), a Greek historian wrote of the war between Atlantis and Europe and noted that some of the ancient tribes in France claimed it as their original home. There is some dispute about the French druids’ claim.

Philo of Alexandria (b.15 BC) also known as Philo Judaeus also accepted the reality of Atlantis’ existence.

Strabo (67 BC-23 AD) in his Geographia stated that he fully agreed with Plato assertion that Atlantis was fact rather than fiction.

Plutarch (46-119 AD) wrote about the lost continent in his book Lives, he recorded that both the Phoenicians and the Greeks had visited this island which lay on the west end of the Atlantic.

Pliny the Younger (61-113 AD) is quoted by Frank Joseph as recording the existence of numerous sandbanks outside the Pillars of Hercules as late as 100 AD.

Pomponius Mela (c.100 AD), placed Atlantis in a southern temperate region.

Tertullian (160-220 AD) associated the inundation of Atlantis with Noah’s flood.

Claudius Aelian (170-235 AD) referred to Atlantis in his work The Nature of Animals.

Arnobius (4thcent. AD.), a Christian bishop, is frequently quoted as accepting the reality of Plato’s Atlantis.

Ammianus Marcellinus (330-395 AD), the Greek historian, who wrote about the destruction of Atlantis as an accepted fact by the intelligentsia of Alexandria.

Proclus Lycaeus (410-485 AD), a representative of the Neo-Platonic philosophy, recorded that there were several islands west of Europe. The inhabitants of these islands, he proceeds, remember a huge island that they all came from and which had been swallowed up by the sea. He also writes that the Greek philosopher Crantor saw the pillar with the hieroglyphic inscriptions, which told the story of Atlantis.

Cosmas Indicopleustes (6thcent. AD), a Byzantine geographer, in his Topographica Christiana (547 AD) quotes the Greek Historian, Timaeus (345-250 BC) who wrote of the ten kings of Chaldea [Zhirov p.40]. *[Marjorie Braymer[198.30] wrote that Cosmas was the first to use Plato’s Atlantis to support the veracity of the Bible.]*

.

- taxalata xalasa

- Δημοσιεύσεις: 20703

- Εγγραφή: 27 Αύγ 2021, 20:52

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

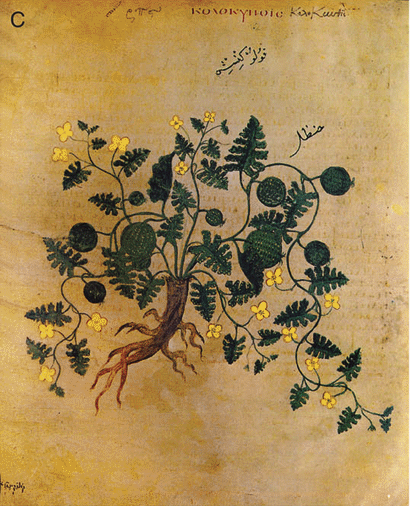

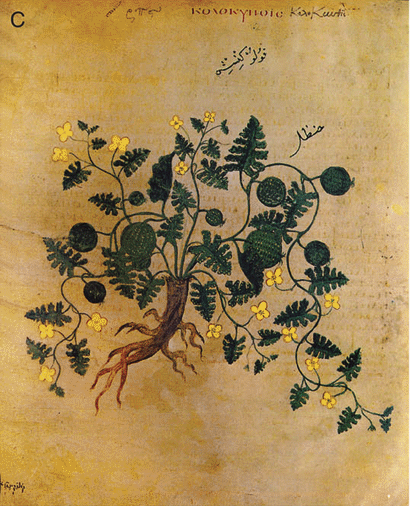

να προσθέσουμε για όσους δεν κατάλαβαν το αίνιγμα της κολοκύθας.

Αυτή είναι η νεροκολοκύθα με έδρα την τροπική Αφρική

και αυτό είναι το κολοκύθι με έδρα την περατλαντική ήπειρο... ονομασία: ayotli.

πως την ήξερε ο Διοσκούριδες;

και πως την ήξερε αιώνες πριν ο Αριστάφανες;

ποιος έχει απάντηση;

πως ήρθε το ayotli από την περατλαντική ήπειρο στον κήπο του Αριστόφανες και του Διοσκούριδες ;

The ancestral species of the genus Cucurbita were present in the Americas before the arrival of humans,[51][52] and are native to the Americas. The likely center of origin is southern Mexico, spreading south through what is now known as Mesoamerica, into South America, and north to what is now the southwestern United States....

Evidence of domestication of Cucurbita goes back over 8,000 years from the southernmost parts of Canada down to Argentina and Chile. Centers of domestication stretch from the Mississippi River watershed and Texas down through Mexico and Central America to northern and western South America

Αυτή είναι η νεροκολοκύθα με έδρα την τροπική Αφρική

και αυτό είναι το κολοκύθι με έδρα την περατλαντική ήπειρο... ονομασία: ayotli.

πως την ήξερε ο Διοσκούριδες;

και πως την ήξερε αιώνες πριν ο Αριστάφανες;

ποιος έχει απάντηση;

πως ήρθε το ayotli από την περατλαντική ήπειρο στον κήπο του Αριστόφανες και του Διοσκούριδες ;

The ancestral species of the genus Cucurbita were present in the Americas before the arrival of humans,[51][52] and are native to the Americas. The likely center of origin is southern Mexico, spreading south through what is now known as Mesoamerica, into South America, and north to what is now the southwestern United States....

Evidence of domestication of Cucurbita goes back over 8,000 years from the southernmost parts of Canada down to Argentina and Chile. Centers of domestication stretch from the Mississippi River watershed and Texas down through Mexico and Central America to northern and western South America

Πολλών δ’ ανθρώπων ίδεν άστεα και νόον έγνων.

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Ευκολακι

Tο κολοκυθι το εφεραν οι Μινωιτες - μαζι με το χαλκο των μεγαλων λιμνων

Tο κολοκυθι το εφεραν οι Μινωιτες - μαζι με το χαλκο των μεγαλων λιμνων

ΖΗΝΗΔΕΩΣ

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Μινωιτες, Μυκηναιοι, Ατλαντες.

Ειναι απο τις περιπτωσεις που οτι και να διαλεξει η αντιπαλη παρεα χανει.

.

Ειναι απο τις περιπτωσεις που οτι και να διαλεξει η αντιπαλη παρεα χανει.

.

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

αυτο που εχουμε σαν αποδειξη ειναι απο μινωιτες ή και απο τους προ-μινωιτες

δεν υπαρχουν ενδειξεις απο ατλαντες ισως οι γνωστοι μινωες να ηταν τα απομειναρια ενος μεγαλυτερου

πολιτισμου και φυσικα τα ταξιδια τοτε ηταν πιο ευκολα να γινουν αφου η θαλασσα ηταν πιο χαμηλα

βρεθηκε μινωικος ταφος στην πυλο με σφραγιδες και χρυσα ασυλητος που σημαινει παρουσια

μινωιτων μεχρι και πριν απο 5 με 6 χιλ χρονια

δεν υπαρχουν ενδειξεις απο ατλαντες ισως οι γνωστοι μινωες να ηταν τα απομειναρια ενος μεγαλυτερου

πολιτισμου και φυσικα τα ταξιδια τοτε ηταν πιο ευκολα να γινουν αφου η θαλασσα ηταν πιο χαμηλα

βρεθηκε μινωικος ταφος στην πυλο με σφραγιδες και χρυσα ασυλητος που σημαινει παρουσια

μινωιτων μεχρι και πριν απο 5 με 6 χιλ χρονια

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Αρίστος έγραψε: ↑12 Ιουν 2024, 13:53Ειναι ενα απο τα πιο συγκλονιστικα αποσπασματα της αρχαιας ελληνικης γραμματειας.

Η απεναντι ηπειρος του πλατωνικου κειμενου ειναι η Αμερικη.

«Τα αρχεία μας αναφέρουν ότι η πόλη σας αναχαίτισε κάποτε μια μεγάλη δύναμη που είχε επιτεθεί με αλαζονεία εναντίον όλης της Ευρώπης και της Ασίας ξεκινώντας απ' έξω, από τον Ατλαντικό ωκεανό. Οι άνθρωποι μπορούσαν να ταξιδεύουν εκείνη την εποχή στον ωκεανό, γιατί αμέσως μετά το στόμιό του ―που, όπως μαθαίνω, εσείς το ονομάζετε Ηράκλειες Στήλες― υπήρχε ένα νησί μεγαλύτερο από την Ασία και τη Λιβύη μαζί. Οι ταξιδιώτες της εποχής περνούσαν από αυτό στα άλλα νησιά και από εκεί σε όλη την απέναντι ήπειρο που περιβάλλει αυτήν την πραγματικά αχανή θάλασσα. Όλα τα μέρη που βρίσκονται μέσα από το στόμιο που λέγαμε φαίνονται σαν λιμάνι με στενή είσοδο• το πέλαγος όμως που εκτείνεται έξω από το στόμιο είναι πραγματικό πέλαγος• και η στεριά που το περικλείει θα έλεγε κανείς ότι αξίζει να ονομαστεί "ήπειρος", στην κυριολεξία του όρου».

Και πιο κατω το κειμενο λεει για τους Ατλαντες που κατεκτησαν μερη της Αμερικης.

«Σ' αυτό το νησί, την Ατλαντίδα, δημιουργήθηκε κάτω από βασιλική εξουσία μια μεγάλη και θαυμαστή δύναμη που κυριάρχησε σε όλο το νησί καθώς και σε πολλά άλλα νησιά και μέρη της απέναντι ηπείρου. Επιπλέον, προς την πλευρά μας, επικράτησε στη Λιβύη ως την Αίγυπτο και στην Ευρώπη ως την Τυρρηνία».

Τίμαιος 24e-25b, μετάφραση Β. Κάλφα.

.

Μπορεί να αναφέρεται στη Βρετανία. Ο Πυθέας που δεν είναι πολύ απομακρυσμένος από τον Πλάτωνα χρονολογικά έγραψε για ταξίδι στη Βρετανία και πιθανώς στην Ισλανδία. Δεν ξέρω ακριβώς όταν έλαβε χώρο το ταξίδι του αλλά ίσως όταν ο Πλάτων ήταν ακόμη ζωντανός.

https://el.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/%CE%A0% ... E%B7%CF%82

Τελευταία επεξεργασία από το μέλος τίποτα την 17 Ιουν 2024, 15:19, έχει επεξεργασθεί 1 φορά συνολικά.

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Δεν πιστεύω όμως ότι ο μύθος είναι αληθινός, αλλά μπορεί να βασίζεται σε αληθινά γεγονότα όπως η γνώση της ύπαρξης της Βρετανίας ή ίσως της Αμερικής και αναφορές για τη κατάρρευση της Θήρας, που ο Πλάτων ανακάτεψε όταν δημιούργησε τον μύθο.

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Δεν δημιουργησε ο Πλατωνας το μυθο, αν δεις τη λιστα με τους αρχαιους Ελληνες και Ρωμαιους που εβαλα, η γενικη πεποιθηση ηταν πως η ιστορια αποτελουσε καταγραφη των οσων ειπαν οι Αιγυπτιοι ιερεις στο Σολωνα.

Και συμφωνα με τον Αμμιανο Μαρκελινο ολοι οι λογιοι της Αλεξανδρειας, που ειχαν στη διαθεση τους και την περιφημη Βιβλιοθηκη, πιστευαν πως η ιστορια ηταν αληθινη.

.

Και συμφωνα με τον Αμμιανο Μαρκελινο ολοι οι λογιοι της Αλεξανδρειας, που ειχαν στη διαθεση τους και την περιφημη Βιβλιοθηκη, πιστευαν πως η ιστορια ηταν αληθινη.

.

- omg kai 3 lol

- Δημοσιεύσεις: 7445

- Εγγραφή: 03 Απρ 2018, 14:03

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Αρίστος έγραψε: ↑17 Ιουν 2024, 15:26Δεν δημιουργησε ο Πλατωνας το μυθο, αν δεις τη λιστα με τους αρχαιους Ελληνες και Ρωμαιους που εβαλα, η γενικη πεποιθηση ηταν πως η ιστορια αποτελουσε καταγραφη των οσων ειπαν οι Αιγυπτιοι ιερεις στο Σολωνα.

Και συμφωνα με τον Αμμιανο Μαρκελινο ολοι οι λογιοι της Αλεξανδρειας, που ειχαν στη διαθεση τους και την περιφημη Βιβλιοθηκη, πιστευαν πως η ιστορια ηταν αληθινη.

ειναι ολοφανερο οτι ο Πλατωνας εγραψε ολοκληρο "Τιμαιο" και "Πολιτεια" για να αναδειξει τους Ατλαντες, με αυτους πραγματευεται στα εργα του και αυτοι ηταν και το επιμυθιο

και οχι δεν ανεφερε τους αιγυπτιους ιερεις ως "αυθεντιες-μπλοφες" για να γινει πιο πειστικος στο παραμυθι του λες και υπηρχε κανενας αιγυπτιος ιερεας που ειδε τους ατλαντες για να συμφωνησει ή να τον διαψευσει

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Ναι ολοι οι αρχαιοι Ελληνες και οι Ρωμαιοι συνωμοτησαν για να βγαλουν την ιστορια του Πλατωνα αληθινη και ο ιδιος ο Πλατωνας ειπε ρε αφου θα μας παρουν χαμπαρι κατσε να βαλω την Αμερικη μεσα μπας και μας πιστεψουν.

.

.

- omg kai 3 lol

- Δημοσιεύσεις: 7445

- Εγγραφή: 03 Απρ 2018, 14:03

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

κανεις δε συνομωτησε, ο Πλατωνας δημιουργησε σχολες σκεψης και οι μεταγενεστεροι του τον επικαλουνται ως "αυθεντια" εως και σημερα για καποιες αποψεις του που θεωρουνται δικαιως ή αδικως ως "θεσφατα", με τον ιδιο τροπο που επικαλεστηκε κι εκεινος ως "αυθεντιες" της εποχης, τους αιγυπτιους ιεριεις μονο που εκεινοι δεν αφησαν καμια αντιστοιχη παρακαταθηκη

- omg kai 3 lol

- Δημοσιεύσεις: 7445

- Εγγραφή: 03 Απρ 2018, 14:03

Re: Όταν ο Πλάτωνας έγραφε για Άτλαντες στην Αμερική

Αρίστος έγραψε: ↑17 Ιουν 2024, 08:47Αντε να βαλουμε και το λουκουμο στο νημα.

Ενα σκασμο αρχαιους Ελληνες και Ρωμαιους λογιους που οχι μονο θεωρουσαν σαν αληθινη την ιστορια του Πλατωνα για την Ατλαντιδα αλλα καποιοι συμπληρωσαν και επιπλεον στοιχεια.

Κανονιστε γιδια να τους βγαλετε ψεκες, θεοσοφιστες η ναζι.

Syrianus (died c.437 BC) the neoplatonist and one-time head of Plato’s Academy in Athens, considered Atlantis to be an historical fact. He wrote a commentary on Timaeus, now lost, but his views are recorded by Proclus.

Eumelos of Cyrene (c.400 BC) was a historian and contemporary of Plato’s who placed Atlantis in the central Mediterranean between Libya and Sicily.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Plato’s pupil is constantly quoted in connection with his alleged criticism of Plato’s story. This claim was not made until 1819, when Delambre misinterpreted a commentary on Strabo by Isaac Casaubon. This error has been totally refuted by Thorwald C. Franke[880]. Furthermore it was Aristotle who stated that the Phoenicians knew of a large island in the Atlantic known as ’Antilia’.

Crantor (4th-3rdcent. BC) was Plato’s first editor who reported visiting Egypt where he claimed to have seen a marble column carved with hieroglyphics about Atlantis.

Theophrastus of Lesbos (370-287 BC) refers to colonies of Atlantis in the sea.

Theopompos of Chios (born c.380 BC), a Greek historian – wrote of the huge size of Atlantis and its cities of Machimum and Eusebius and a golden age free from disease and manual labour. Zhirov states [458.38/9] that Theopompos was considered a fabulist.

Apollodorus of Athens (fl. 140 BC) who was a pupil of Aristarchus of Samothrace (217-145 BC) wrote “Poseidon was very wrathful, and flooded the Thraisian plain, and submerged Attica under sea-water.” Bibliotheca, (III, 14, 1.)

Poseidonius (135-51 BC.) was Cicero’s teacher and wrote, “There were legends that beyond the Hercules Stones there was a huge area which was called “Poseidonis” or “Atlanta”

Diodorus Siculus (1stcent. BC), the Sicilian writer who has made a number of references to Atlantis.

Marcellus (c.100 BC) in his Ethiopic History quoted by Proclus [Zhirov p.40] refers to Atlantis consisting of seven large and three smaller islands.

Statius Sebosus (c. 50 BC), the Roman geographer, tells us that it was forty days’ sail from the Gorgades (the Cape Verdes) and the Hesperides (the Islands of the Ladies of the West, unquestionably the Caribbean).

Timagenus (c.55 BC), a Greek historian wrote of the war between Atlantis and Europe and noted that some of the ancient tribes in France claimed it as their original home. There is some dispute about the French druids’ claim.

Philo of Alexandria (b.15 BC) also known as Philo Judaeus also accepted the reality of Atlantis’ existence.

Strabo (67 BC-23 AD) in his Geographia stated that he fully agreed with Plato assertion that Atlantis was fact rather than fiction.

Plutarch (46-119 AD) wrote about the lost continent in his book Lives, he recorded that both the Phoenicians and the Greeks had visited this island which lay on the west end of the Atlantic.

Pliny the Younger (61-113 AD) is quoted by Frank Joseph as recording the existence of numerous sandbanks outside the Pillars of Hercules as late as 100 AD.

Pomponius Mela (c.100 AD), placed Atlantis in a southern temperate region.

Tertullian (160-220 AD) associated the inundation of Atlantis with Noah’s flood.

Claudius Aelian (170-235 AD) referred to Atlantis in his work The Nature of Animals.

Arnobius (4thcent. AD.), a Christian bishop, is frequently quoted as accepting the reality of Plato’s Atlantis.

Ammianus Marcellinus (330-395 AD), the Greek historian, who wrote about the destruction of Atlantis as an accepted fact by the intelligentsia of Alexandria.

Proclus Lycaeus (410-485 AD), a representative of the Neo-Platonic philosophy, recorded that there were several islands west of Europe. The inhabitants of these islands, he proceeds, remember a huge island that they all came from and which had been swallowed up by the sea. He also writes that the Greek philosopher Crantor saw the pillar with the hieroglyphic inscriptions, which told the story of Atlantis.

Cosmas Indicopleustes (6thcent. AD), a Byzantine geographer, in his Topographica Christiana (547 AD) quotes the Greek Historian, Timaeus (345-250 BC) who wrote of the ten kings of Chaldea [Zhirov p.40]. *[Marjorie Braymer[198.30] wrote that Cosmas was the first to use Plato’s Atlantis to support the veracity of the Bible.]*

πολλες αντικρουομενες αποψεις μαστορα, ο ενας μπλεκει Νωε, ο αλλος τη λεει Αντιλλα ο αλλος 7νησα, ο αλλος την τοποθετει μεταξυ Σικελιας και Λιβυης ο αλλος στη Καραιβικη των χοροεσπεριδων, ο αλλος εμπιστευεται την ιντελιτζενσια της Αλεξανδρειας γενικα υπαρχουν πολλες αντικρουομενες αποψεις με αδιασειστα στοιχεια

ολοι αυτοι αναφερονται στην ατλαντιδα σχεδον με ιστορικη αφελεια σε εποχες που ο κοσμος αδιαφορουσε για την υπαρξη της

η ατλαντιδα και η αρεια φυλη επανηλθε οταν η επιστημη, που ακομα δεν ηταν κανονικη επιστημη, παρολαυτα μοιραζε εγκεφαλικα στις θρησκειες και καποιοι επιτηδειοι καταλαβαν οτι εκει υπαρχει μπολικο ψωμακι, ενας απο αυτους ηταν και ο αδολφος

και αφου εγινε οτι εγινε, μετα οι πονηριδηδες βιβλιοπωλες ντανικεν-χανκοκ και κακο συναπαντημα εβγαλαν την αρεια φυλη απο την εξισωση, για να μη τους πουν παλι ναζοφασιστες, και εβαλαν τους εξωγηινους

ελα ομως που ολες οι πηγες και οι αναφορες τους παραμενουν απο τα θεοσοφοναζιστοπουλα, ο κουτοπονηρος αριστος πεταει κι ενα Διοδωρο κι ενα Πλινιο που και που για ξεκαρφωμα, για να σπαει η δυσοσμια, μεχρι εκει

-

- Παραπλήσια Θέματα

- Απαντήσεις

- Προβολές

- Τελευταία δημοσίευση

-

-

Νέα δημοσίευση Tα drones που εμφανίστηκαν στην Αμερική τώρα και στην Ευρώπη

από Αρίστος » 13 Δεκ 2024, 19:01 » σε Εναλλακτικές επιστήμες - 37 Απαντήσεις

- 1896 Προβολές

-

Τελευταία δημοσίευση από The Rebel

20 Δεκ 2024, 20:52

-

-

- 86 Απαντήσεις

- 4879 Προβολές

-

Τελευταία δημοσίευση από Γράφων

15 Φεβ 2024, 15:32

-

-

Νέα δημοσίευση Ιταλικο Ιδρυμα Ερευνων: Βρηκαμε που ενταφιάστηκε ο Πλάτωνας

από George_V » 23 Απρ 2024, 13:47 » σε Αρχαιολογία - 2 Απαντήσεις

- 1018 Προβολές

-

Τελευταία δημοσίευση από Σενέκας

23 Απρ 2024, 14:11

-

-

- 1 Απαντήσεις

- 275 Προβολές

-

Τελευταία δημοσίευση από Ληστοσυμμορίτης

03 Ιαν 2025, 19:17