As the Euro Turns 20, a Look Back at Who Fared the Best. And Worst.

By Andre Tartar, Cindy Hoffman and Paul Murray

28 December 2018

Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, once likened the euro to a bumblebee—a “mystery of nature” that shouldn’t be able to fly, but somehow does.

Draghi used this metaphor at the height of the tumultuous Greek debt crisis in 2012, when many wondered if the demise of Europe’s single currency was imminent.

Now, two decades after its birth, the euro has taken flight and, by some measures, has even soared. Membership has grown to 19 countries from the original 11, and the size of the euro-area economy has swelled by 72 percent to 11.2 trillion euros ($12.8 trillion), second only to that of the U.S. and positioning the European Union as a global force to be reckoned with.

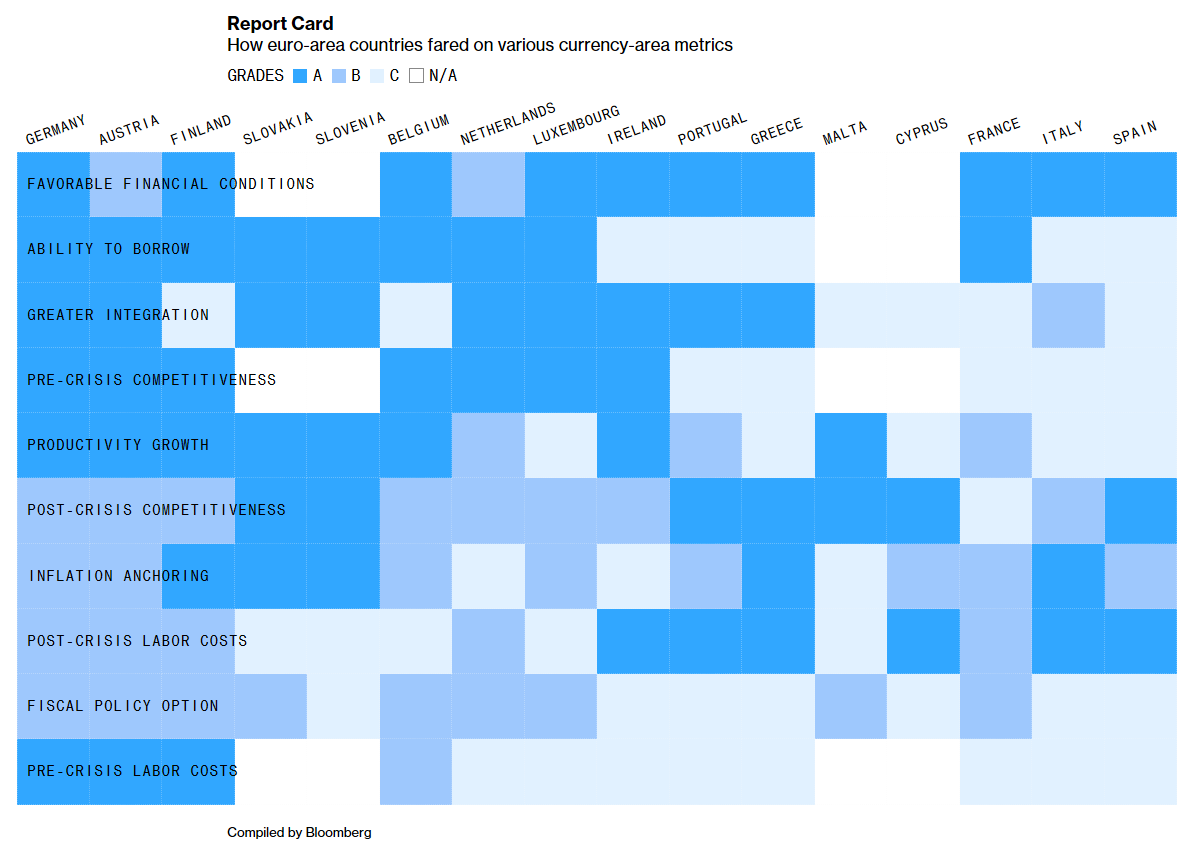

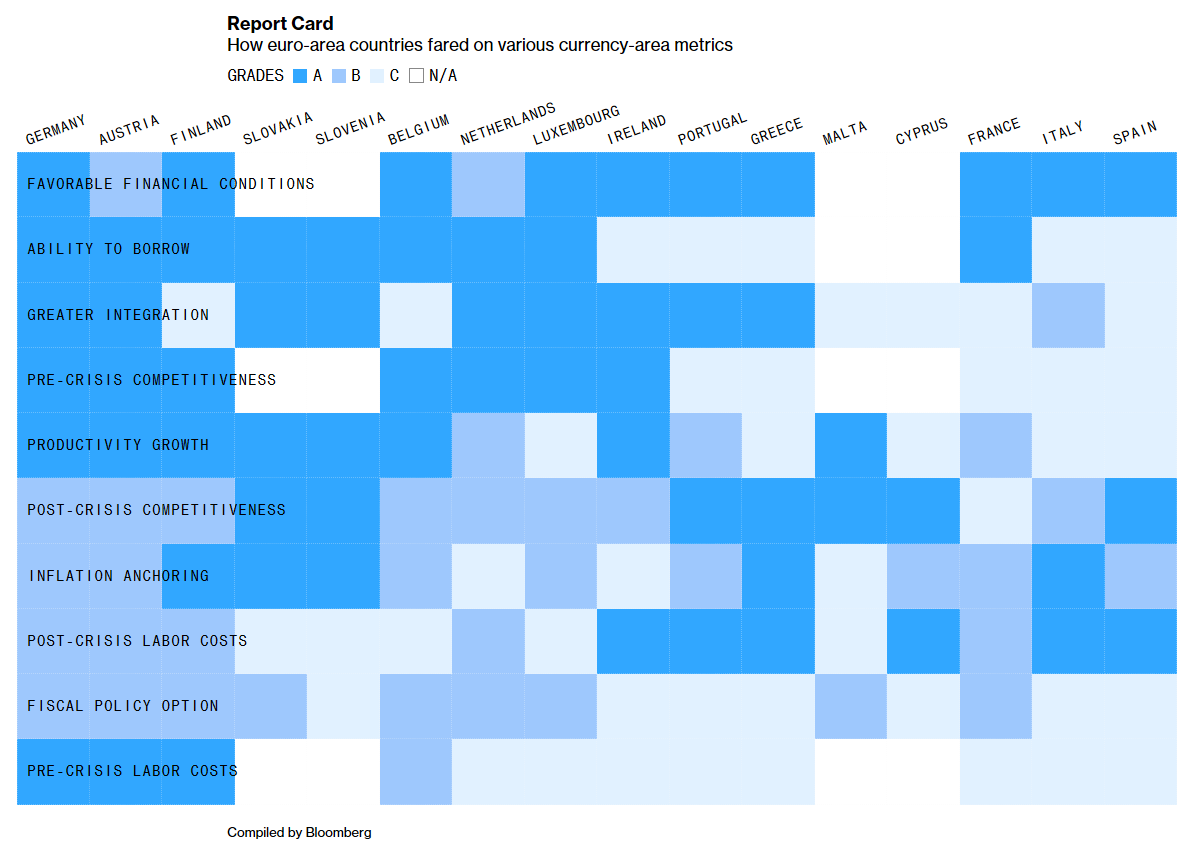

This achievement masks divergences that were perhaps impossible to avoid for a region of such enormous economic and cultural diversity. When European nations traded in the power to set their own interest rates and submitted to the bloc’s fiscal limits, they were counting on greater economic welfare to follow. Bloomberg created a series of tests for the euro’s 20th anniversary to see how they did. The results, outlined in illustrations below, show only a handful are clearly flourishing.

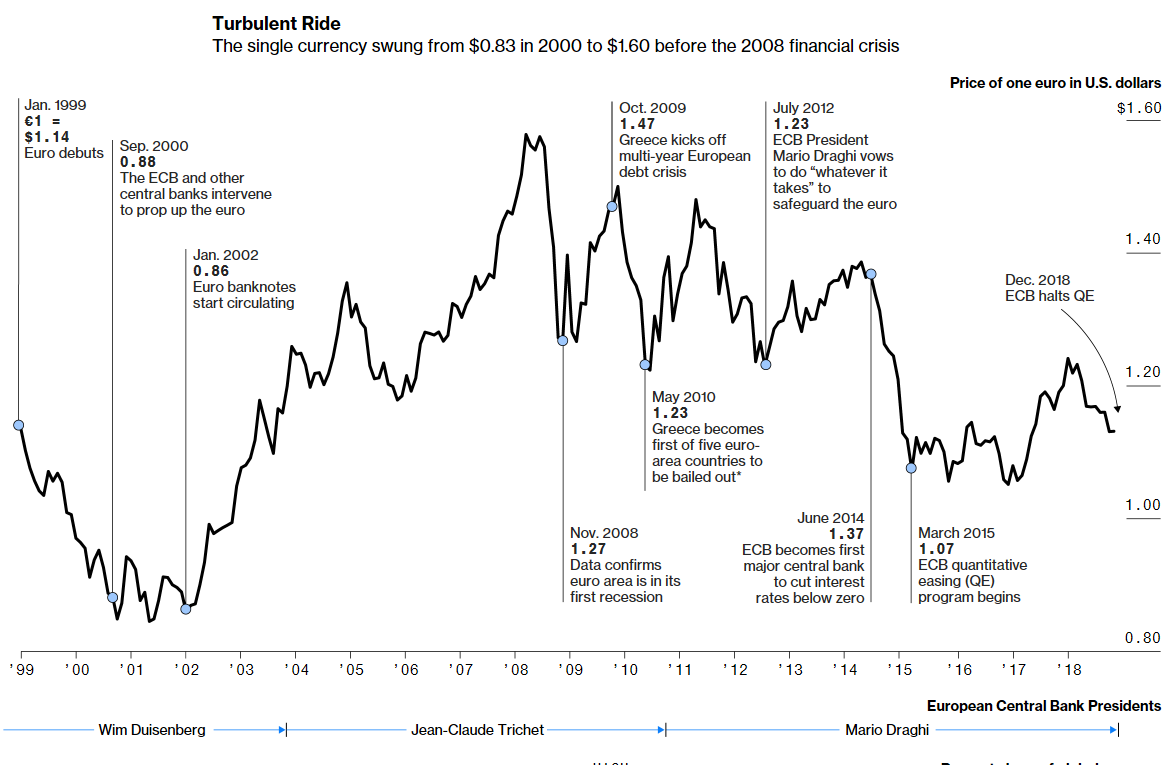

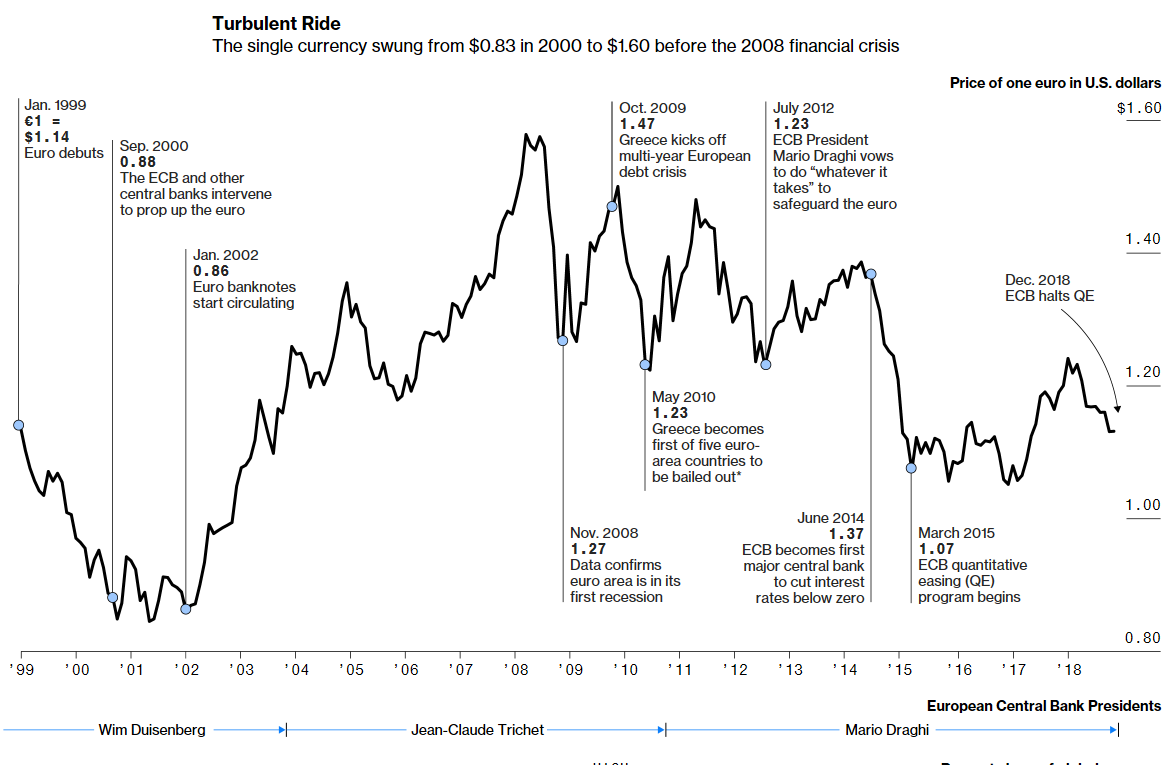

The euro has swung wildly since its debut on Jan. 1, 1999, three years before notes and coins went into circulation. It’s been especially turbulent this decade as bailouts of debt-laden members and a double-dip recession nearly tore the monetary union apart. By flooding the bloc with cash, Draghi managed to keep Europe’s currency dream alive. That didn’t reverse the damage to the euro’s reputation, though; its share of global reserves is down nearly 30 percent since a 2009 peak.

...............................

Satisfactory Grades

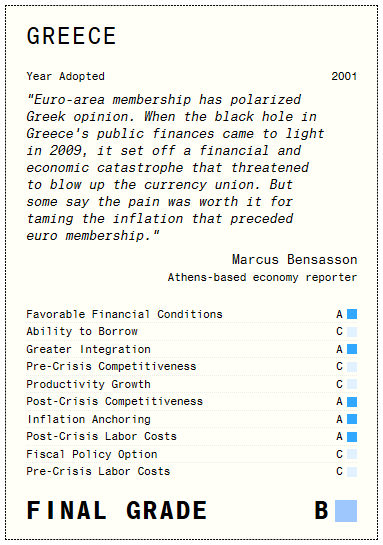

The benefits of monetary union weren’t quite so pronounced for some founding members. While the countries in this category mostly remained externally competitive, when hard times hit, Ireland and Portugal in particular struggled because they didn’t have enough room to maneuver with fiscal policy alone and flirted with deflation. While Greece suffered mightily during the sovereign debt crisis, it also eked out a B.

For all that went wrong, being part of the euro for 18 years made it possible for Greece to build new trade relationships with Europe’s wealthier core. Transferring monetary policy to a credible central bank brought greater price stability in the early years and the recent past has seen a big improvement in competitiveness.

Each indicator was designed so that a positive response received an A grade, a neutral response a B grade and a negative response a C grade. Some criteria only applied to the initial 12 members, and so were left blank for later adopters. For full details, see the methodology at the bottom. A country’s overall score was determined based on how many more As it achieved than Cs, like this:

A 2 or more, very good

B 0 to 1, satisfactory

C -1 or less, mediocre

Next Test

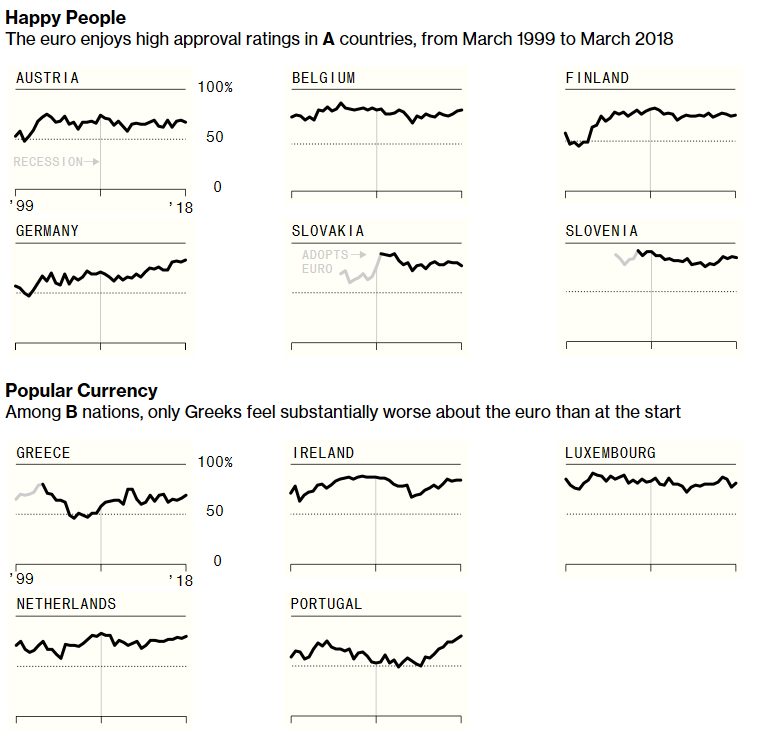

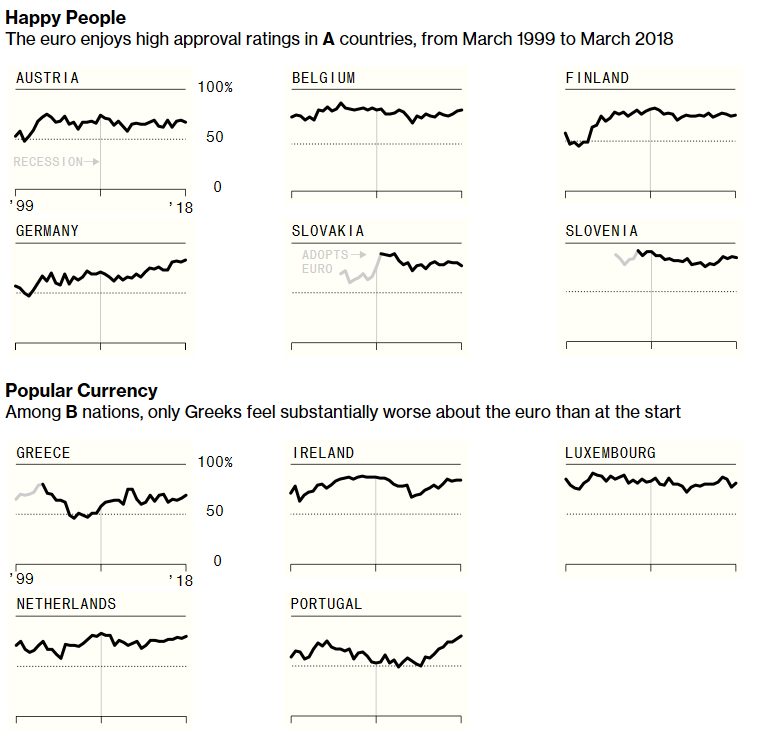

Beyond the economic disparities, there’s something that matters even more for the euro’s future: how Europeans feel about it. The single currency was always part of a broader political project to ensure peaceful coexistence in Europe, bringing people and countries closer together following two world wars.

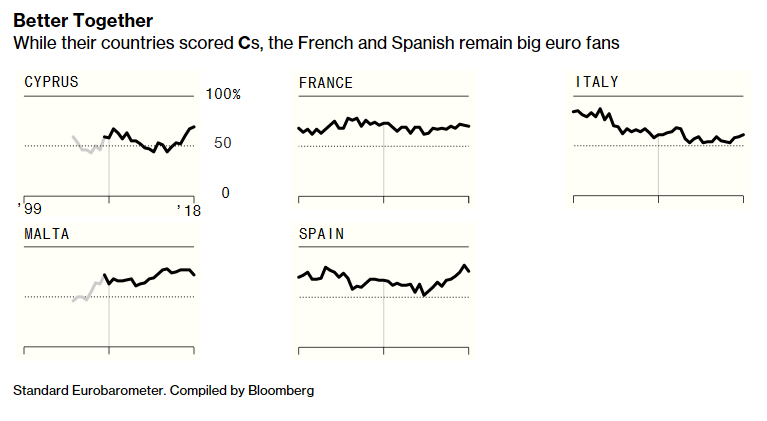

The sovereign debt crisis, the rise of populist radical-right parties and Britain’s vote to leave the EU have tested that cohesion. Polls show popular support for the euro has plunged in Italy, which recently elected an anti-establishment government that spent several months warring with the European Commission over its budget.

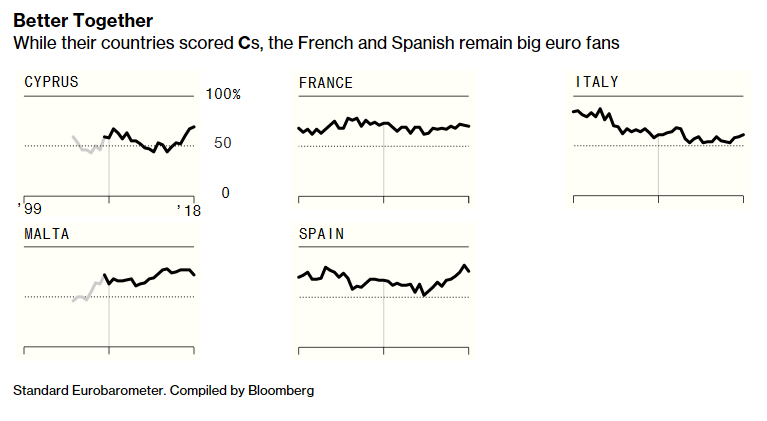

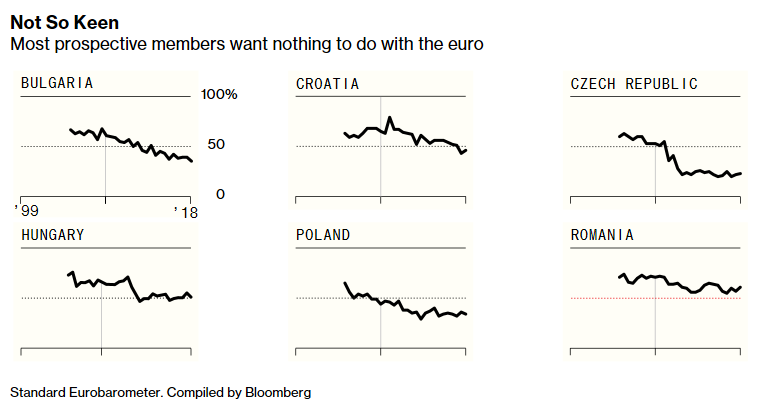

Yet in nations that use the euro, most people are still overwhelmingly fans. Sentiment has improved in 13 member states since they joined, with double-digit bumps in Austria, Finland, Germany and Portugal. Even in Italy, which witnessed a roughly 25-point decline, around 60 percent of people favor sharing a currency with their neighbors.

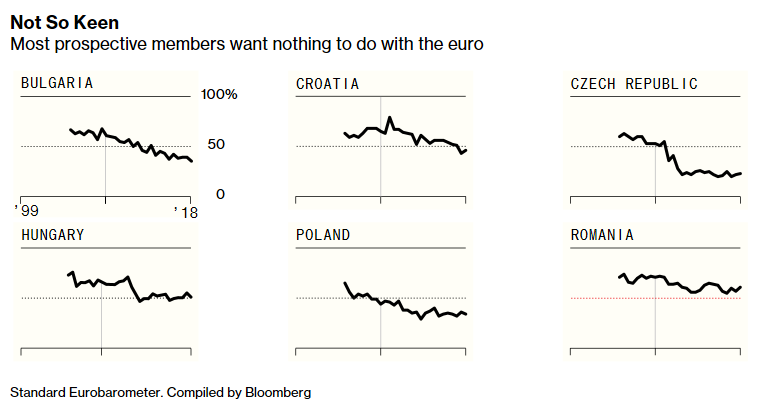

That’s not to say everyone is queuing to join. Polls conducted since 2012 show only 35 percent of Poles and 23 percent of Czechs, on average, are eager to sign up. They, like many Hungarians, are loath to give up their national currencies, even though the EU’s Maastricht Treaty technically requires them to. Among countries eligible for membership, only in Romania does support surpass 60 percent.

For its next decade, then, the euro’s success will hinge a lot on its ability to carry on defying the economic and political odds stacked against it, and keep flying anyways.